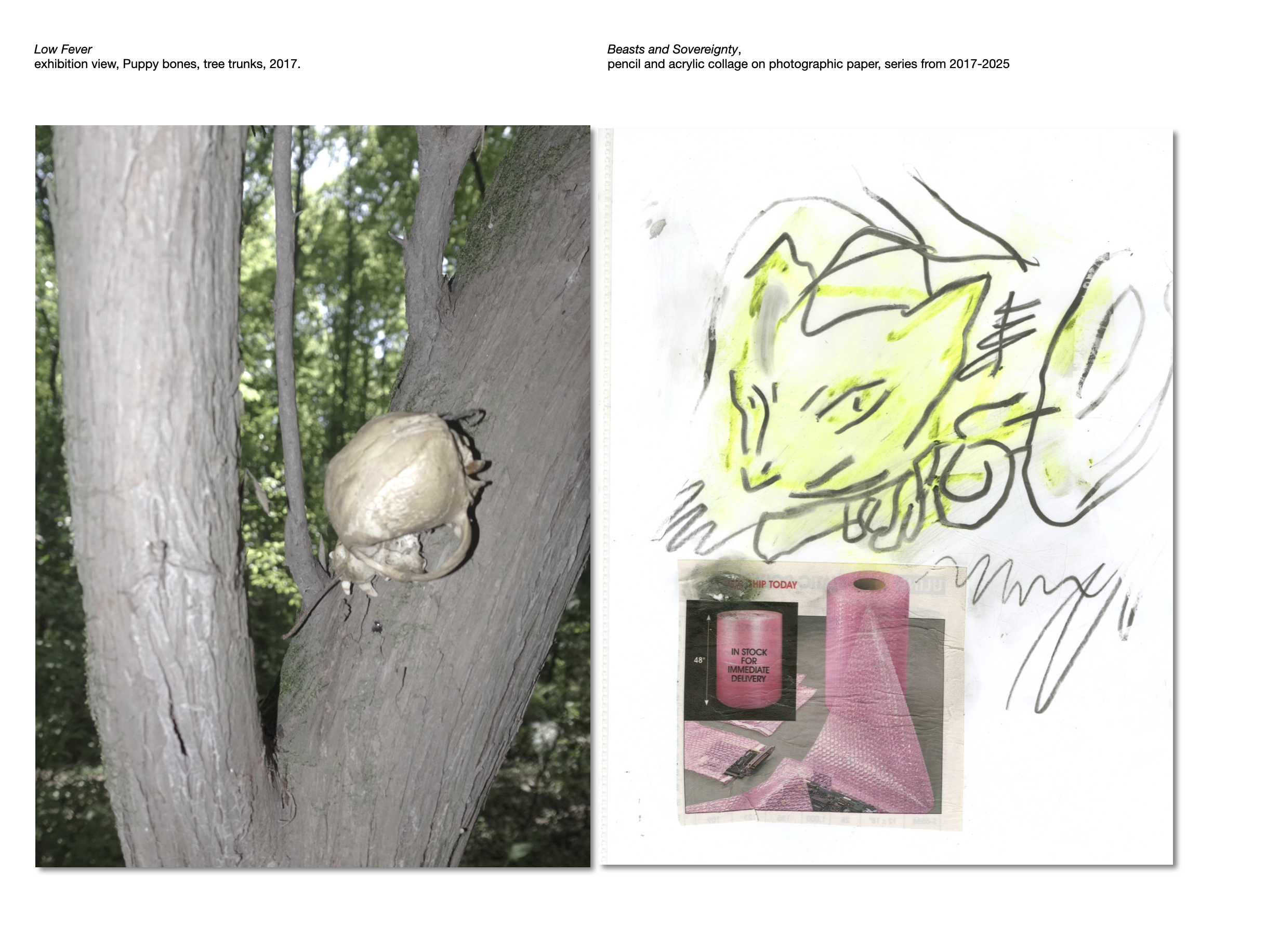

Low Fever, 2017. Exhibition documentation

Low Fever, 2017. Installation view

The artist places vividly colored, anthropomorphic wooden sculptures deep within the forest. Captured under directed lighting in the darkness, conjuring associations with ritual, belief, and collective memory. These sculptures are imbued with an animistic presence, oscillating between the natural and the artificial, the living and the inert. The inclusion of electronic devices enhances the immersive experience and encourages public participation, transforming the encounter into a contemporary communal ritual. This approach aligns with Lucy Lippard’s notion in Public Art: Old and New Clothes, which advocates for art rooted in local histories and ecological contexts, acting as a bridge between people and their environment. Following this framework, the artist envisions their work as a conduit between ancient animistic traditions and the collective rituals of modern society.

Further, the artist incorporates research on wartime infrastructure—bunkers, air raid shelters, and other “preparedness” facilities—treating these as material residues of collective fear and anticipation. These sites, often hidden in natural landscapes or slowly fading from public memory, are physical manifestations of a society’s expectation of disaster. As spatial foreshadowings of collapse, they point to the impossibility of utopia—a future imagined, prepared for, but never attained. In juxtaposing these remnants with forest installations, the work takes on a ghostly archaeological tone, confronting both the mysticism of the past and the unspoken anxieties of the present.

At the heart of the artist’s inquiry is animism—the belief that all things, including plants, objects, and places, possess a spiritual essence. Historically, animistic practices have been rooted in collective rituals, from ancient witchcraft performed around fires to contemporary gatherings such as political protests. The artist draws from their hometown’s Chu cultural heritage, where witchcraft traditions were deeply tied to the veneration of animals such as tigers, snakes, and toads. Ancestors crafted tiger figures from tree branches as talismans, integrating spiritual protection with natural materials. This tradition echoes throughout East Asian art, where mythical beasts often combine features of multiple animals and are richly adorned, reflecting a cultural logic that merges the natural with the supernatural.

Yet the contemporary reactivation of these traditions is not without rupture. When the sculptures appear in the forest’s shadows or within gallery spaces resembling memorial sites, they no longer serve as active ritual objects, but rather as fragments of broken ideals—unable to summon spirits or unite communities. They signify what might be called a failed utopia: a structure of belief or a vision of society that, while once imbued with hope, has collapsed under the weight of history, ideology, or abstraction. All that remains are silent objects, abstract signals, and the desire to witness.

Thus, the project becomes both a memorial for lost belief and a meditation on the precarity of future visions. It evokes the past while anticipating collapse; it constructs community while hinting at its disintegration. Drawing simultaneously from natural spirituality and modern preparedness architecture, the work offers a polyphonic landscape of faith, fear, and fragmented utopias.

Low Fever, 2017. Installation view

Low Fever, 2017. Installation view

Low Fever, 2017. Some sketches and sculptural detail

Low Fever, 2017. Some sketches and sculptural details

Low Fever, 2017. Some sketches and sculptural details Low Fever, 2017. Some sketches and sculptural details

Low Fever, 2017. Some sketches and sculptural details Low Fever, 2017. Some sketches and sculptural details

Low Fever, 2017. Some sketches and sculptural details